Music journalism, books and more

Toronto Songs: Murray McLauchlan's "Down By the Henry Moore"

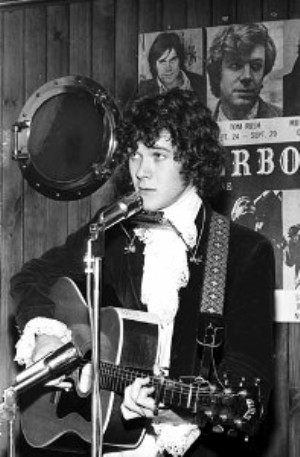

| Murray McLauchlan moved downtown and never looked back. Armed with a guitar and a backpack, he ran away from home at the age of 17 and headed straight to Yorkville. He wound up crashing at the Village Corner coffeehouse, sleeping on a mattress in the basement and soaking up the sounds of guitarists like Amos Garrett and Jim McCarthy and folksingers including Al Cromwell and Elyse Weinberg. The Village Corner had been the place where artists like Ian & Sylvia, Gordon Lightfoot, David Wiffen and Bonnie Dobson all got their start. |

The son of a trade unionist, McLauchlan developed an artistic flair while attending Central Technical School, where he took classes from renowned Canadian painter Doris McCarthy. He also was drawn to literature and music, having absorbed Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Bob Dylan’s first two albums. In particular, he devoured The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. “It had everything in it,” McLauchlan later recalled, “songs that were funny; songs about injustice, love, loss; songs that spoke out against war, but not in a way that just preached at you. They picked you up and carried you along their art. You came to them of your own free will!” It wasn’t long before McLauchlan was writing songs himself.

When he moved downtown, McLauchlan said goodbye to the suburbs and the world of his parents. Instead of a farewell letter, he wrote “Child’s Song,” a coming-of-age number that captured the mixed emotions of leaving home. Another early composition was “Sixteen Lanes of Highway,” which dealt with the loss of his boyhood fields of grass to urban sprawl and the McDonald-Cartier Freeway, known informally as the 401. His sensitive tales of growing up were the first signs that McLauchlan had a promising future as a songwriter.

One of the first people to take notice of McLauchlan’s talent was Tom Rush. An American folksinger, Rush had made a career performing the songs of bluesmen like Willie Dixon and such singer-songwriters as James Taylor, Jackson Browne and Canada’s Joni Mitchell, with whom McLauchlan had shared the stage at the Mariposa Folk Festival in the summer of ’68. That same summer, McLauchlan met Rush, who asked him if he had any songs that might be good for him. There, at Yorkville’s Riverboat coffeehouse, McLauchlan bravely played him “Child’s Song” and “Old Man’s Song,” his stark ode to aging. Almost immediately, Rush announced his intention to record both of them.

One of the first people to take notice of McLauchlan’s talent was Tom Rush. An American folksinger, Rush had made a career performing the songs of bluesmen like Willie Dixon and such singer-songwriters as James Taylor, Jackson Browne and Canada’s Joni Mitchell, with whom McLauchlan had shared the stage at the Mariposa Folk Festival in the summer of ’68. That same summer, McLauchlan met Rush, who asked him if he had any songs that might be good for him. There, at Yorkville’s Riverboat coffeehouse, McLauchlan bravely played him “Child’s Song” and “Old Man’s Song,” his stark ode to aging. Almost immediately, Rush announced his intention to record both of them.

Living downtown, in Toronto’s multicultural Kensington Market neighborhood and later in the city’s working-class Cabbagetown district, exposed McLauchlan to people and places that figured prominently in his new songs. He wrote portraits of the downtown and the downtrodden, of grizzled winos and street people in songs like “Honky Red” and “Ragged Hobo Bums.” These and other streetwise narratives, together with the title of his debut album, Song from the Street, earned McLauchlan an image as an idealistic inner-city poet.

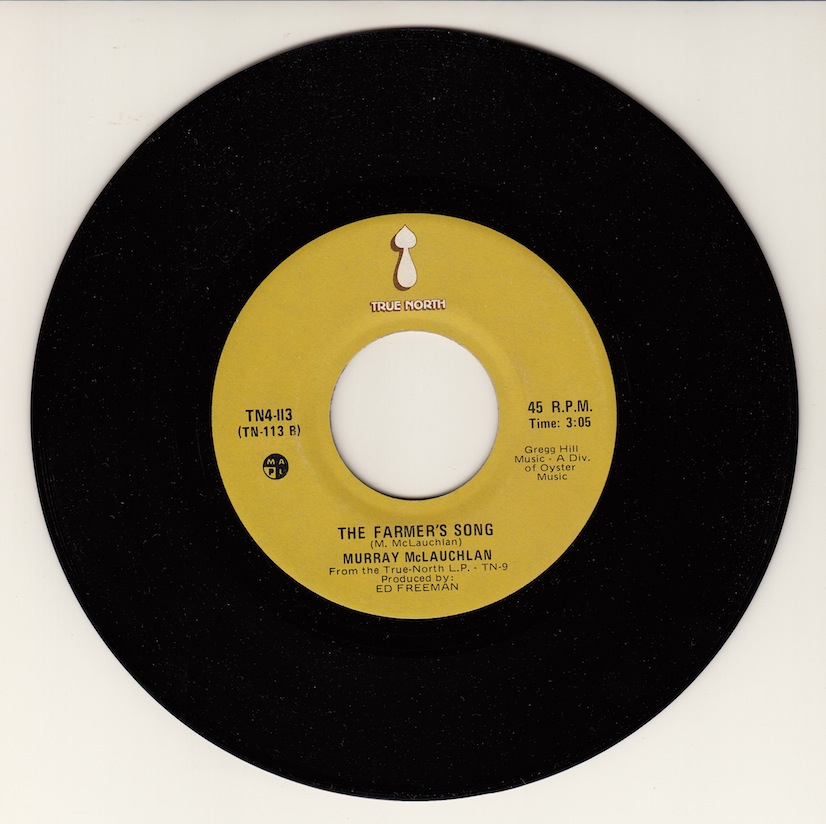

McLauchlan’s best-known composition, “The Farmer’s Song,” appeared on his second, self-titled album. But even that song, which thanks the people who grow the food we eat, was written from an urban perspective. “Thanks for the meal here’s a song that is real,” McLauchlan sings, “From a kid from the city to you.” The song reached the Top 10 in the summer of ’73, earned McLauchlan Juno Awards for composer of the year and top folk and country single. It also took him on a U.S. tour opening for Neil Young and, 20 years later, inspired the Barenaked Ladies’ song “Straw Hat and Old Dirty Hank.”

McLauchlan’s best-known composition, “The Farmer’s Song,” appeared on his second, self-titled album. But even that song, which thanks the people who grow the food we eat, was written from an urban perspective. “Thanks for the meal here’s a song that is real,” McLauchlan sings, “From a kid from the city to you.” The song reached the Top 10 in the summer of ’73, earned McLauchlan Juno Awards for composer of the year and top folk and country single. It also took him on a U.S. tour opening for Neil Young and, 20 years later, inspired the Barenaked Ladies’ song “Straw Hat and Old Dirty Hank.”

McLauchlan’s stature as a songwriter was on the rise. Increasingly, he was hanging out with the likes of Gordon Lightfoot, Kris Kristofferson and Rita Coolidge. After performing at the Philadelphia Folk Festival in 1973, his hotel room became the scene of illustrious jam sessions, featuring Tom Waits, John Prine, Jim Croce, Steve Goodman and Loudon Wainwright III, all trading stories and swapping songs.

When he wasn’t on tour, McLauchlan was enjoying the city life in Toronto. For a time, he lived on Augusta Avenue in Kensington Market, with its vintage clothing stores, Jamaican record shops and fresh fruit and vegetable stores catering to myriad ethnicities. Then he moved to Parliament Street in Cabbagetown, where he lived above the Fix-It-Yourself garage. Before that, he lived in a hippie commune in the heart of Yorkville, at 127 Hazelton Avenue (one of his roommates was the secretary-treasurer of the Vagabonds motorcycle club). As a songwriter, living amid the sights, sounds and smells of these neighborhoods was simply grist for his mill.

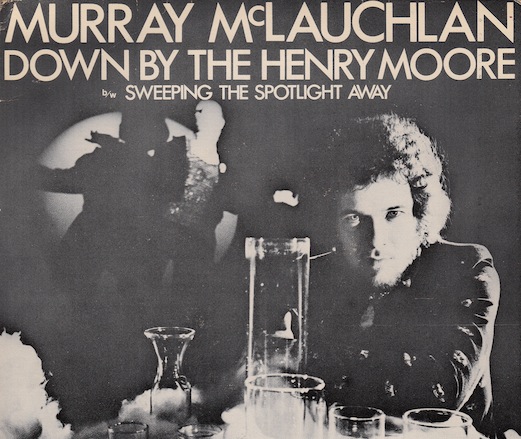

It was on McLauchlan’s fourth album, 1974’s Sweeping the Spotlight Away, that all of his observations about the people, places and things in his hometown came together. One of the  numbers, “Shoeshine Workin’ Song,” dealt with a long-faced street kid who’s beaten by his alcoholic father (it predated by several years the tragic tale of Emmanuel Jacques, the shoeshine boy on Yonge Street whose murder shocked Toronto to its civic core). It also included poignant songs of hope like “Do You Dream of Being Somebody” and “Maybe Tonight,” about a travelling salesman whose only wish is to meet “a stewardess and a glass of booze” at his lonely motel.

numbers, “Shoeshine Workin’ Song,” dealt with a long-faced street kid who’s beaten by his alcoholic father (it predated by several years the tragic tale of Emmanuel Jacques, the shoeshine boy on Yonge Street whose murder shocked Toronto to its civic core). It also included poignant songs of hope like “Do You Dream of Being Somebody” and “Maybe Tonight,” about a travelling salesman whose only wish is to meet “a stewardess and a glass of booze” at his lonely motel.

The album’s most celebratory number was also its most explicitly Toronto-centric song. “Down By the Henry Moore,” with its references to skating at City Hall (where the Henry Moore sculpture “The Archer” is located), shopping in Kensington Market and drinking at the Silver Dollar tavern, was McLauchlan’s shout-out to his hometown. “I wrote that as a sort of travelogue to make people feel good about Toronto,” he says. “A lot of my friends were complaining that there was nothing happening in the city. I believe you can always find something to do if you look for it. So I decided to write a strutting-around-Toronto song to say it’s up to you: you can either enjoy yourself or dump on everything.”

Colin Linden, who covered the song as a member of Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, calls “Henry Moore” a “quintessential Toronto song,” while his Blackie bandmate Tom Wilson credits McLauchlan with giving Torontonians a song of their own, instead of just another ode to New York or Los Angeles. Says Wilson: “Murray was one of the first artists to really step up to the plate and do that.”

Colin Linden, who covered the song as a member of Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, calls “Henry Moore” a “quintessential Toronto song,” while his Blackie bandmate Tom Wilson credits McLauchlan with giving Torontonians a song of their own, instead of just another ode to New York or Los Angeles. Says Wilson: “Murray was one of the first artists to really step up to the plate and do that.”

“I went down to the Henry Moore,” sings McLauchlan, “skated all in the square. The moon above my shoulders, and the ice was in my hair. Alone but never lonely, that’s how I like to be. If I want to have fun like a rock ’n’ roll bum don’t think the worst of me.” With his unabashed anthem to his hometown, Torontonians thought the best of McLauchlan. The city kid with a gift for singing songs about the urban characters around him had become a local folk hero himself.