Gordon Lightfoot Book, Music and More!

George Olliver - Blue-Eyed Prince of Soul

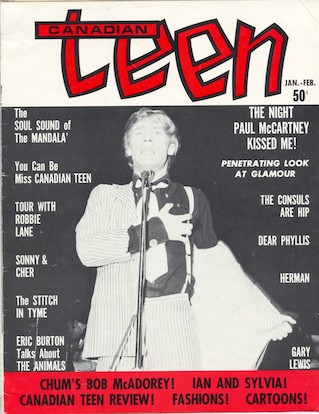

In the mid-1960s, Toronto was teeming with pop groups and teenagers inspired by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. One of the city’s most popular bands, however, took its cues not from the British Invasion but from the rhythm-and-blues sound of American artists such as Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett. That band was the Mandala.

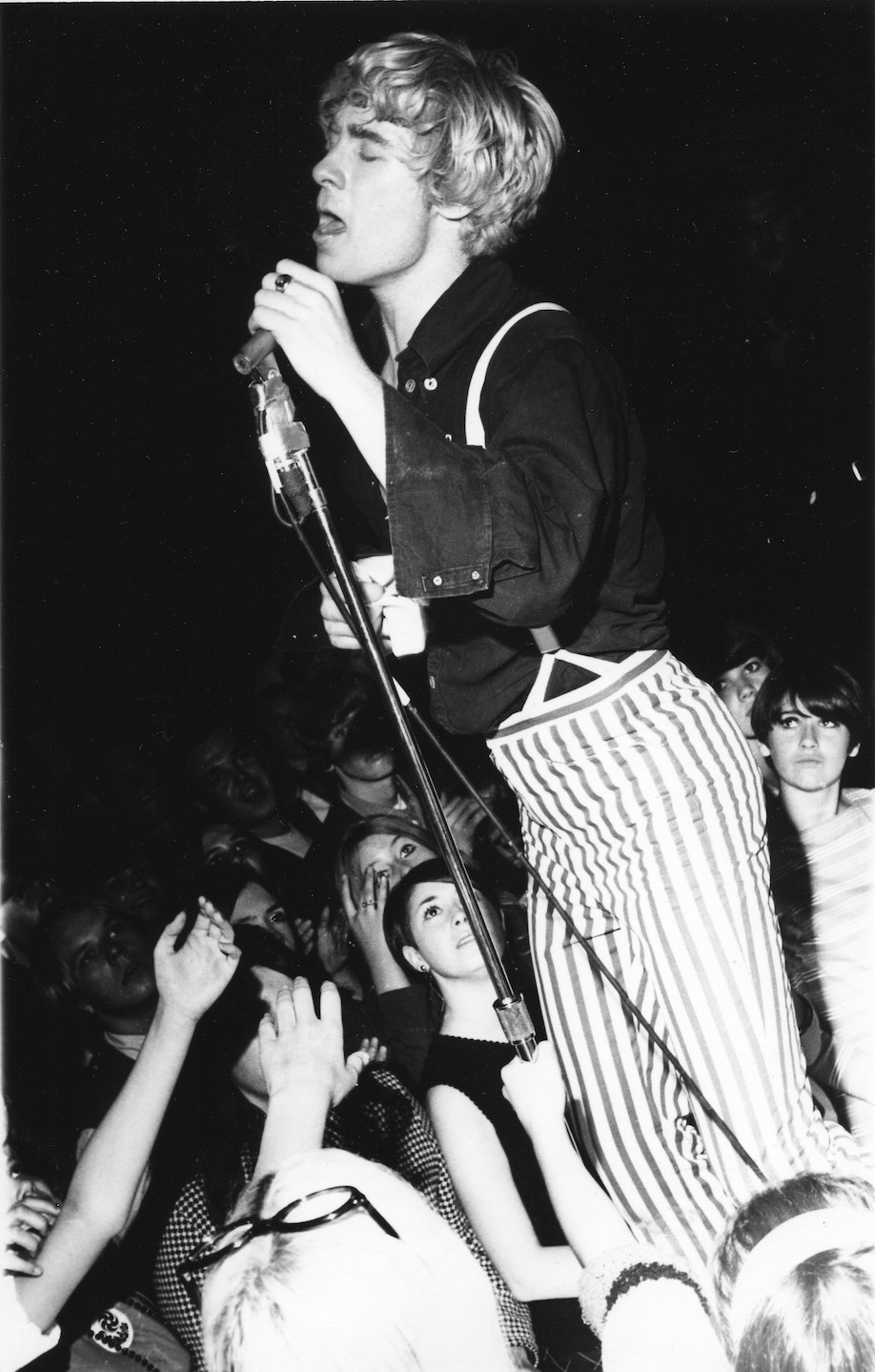

With a dazzling stage show featuring choreography, strobe lights and sonic effects, the Mandala became a sudden sensation. Dressed like costumed gangsters in striped suits, black shirts and white ties, the five members took their self-styled “soul crusade” across Canada, down to New York and out to Los Angeles, earning rave reviews for fever-pitched concerts that critics likened more to gospel revivals than rock concerts.

Much of the attention focused on the Mandala’s blond-haired front man, singer George Olliver, who modelled himself on his hero James Brown. Olliver’s soulful yelps and howls and, especially, his dizzying dance moves – splits, triple pirouettes, back and knee drops and microphone twirls – were a big part of the band’s appeal. But it was his sermonizing, show-stopping “Five Steps to Soul” routine that always won over audiences, ending with the singer giving away his white tie, a symbol of his “soul,” to the outstretched hands of the band’s writhing congregation.

Much of the attention focused on the Mandala’s blond-haired front man, singer George Olliver, who modelled himself on his hero James Brown. Olliver’s soulful yelps and howls and, especially, his dizzying dance moves – splits, triple pirouettes, back and knee drops and microphone twirls – were a big part of the band’s appeal. But it was his sermonizing, show-stopping “Five Steps to Soul” routine that always won over audiences, ending with the singer giving away his white tie, a symbol of his “soul,” to the outstretched hands of the band’s writhing congregation.

Although Olliver left the Mandala in 1967, he never quit performing and remained stage fit. For 10 years he ran a now legendary R&B venue in Toronto and became a bona-fide preacher, leading his own Christian ministry and gospel group. When Olliver died on April 6 at the age of 79, from complications due to a stroke, musicians and fans mourned the loss of an entertainer who, until quite recently, was still singing and even doing the splits.

“George Olliver was the epitome of Toronto soul,” said Paul Shaffer, long-time bandleader on David Letterman’s TV show, from his New York home. “He was a showman and vocalist worthy of the world stage, but chose to favour Canada with his immense talent.”

Added former Blood, Sweat & Tears front man David Clayton-Thomas, who came up through the same Toronto scene as Olliver and once briefly toured with him: “George was a gentleman, a complete pro who worked the stage just like James Brown and always stayed true to his R&B roots.”

Born in Toronto on Jan. 25, 1946, to George Olliver Sr., a mechanic, and his homemaker wife, Betty, George Olliver was the eldest of the family’s three children. He sang in an Anglican church choir and studied classical piano as a boy until falling for the rock ‘n’ roll sound of Bill Haley & His Comets. While attending Northview Heights Collegiate in Willowdale, he and schoolmate Pentti (Whitey) Glan, formed a series of rock bands like the Cool Cats, with Glan on drums and young George on organ.

But the dulcet tones of R&B singer Little Anthony on Goin’ Out of My Head turned Olliver into an instant soul convert. “I heard that song and said ’this is what I want to sing,‘” he told journalist Bill King. “After that, I quickly got into all the other [soul singers] that came along.”

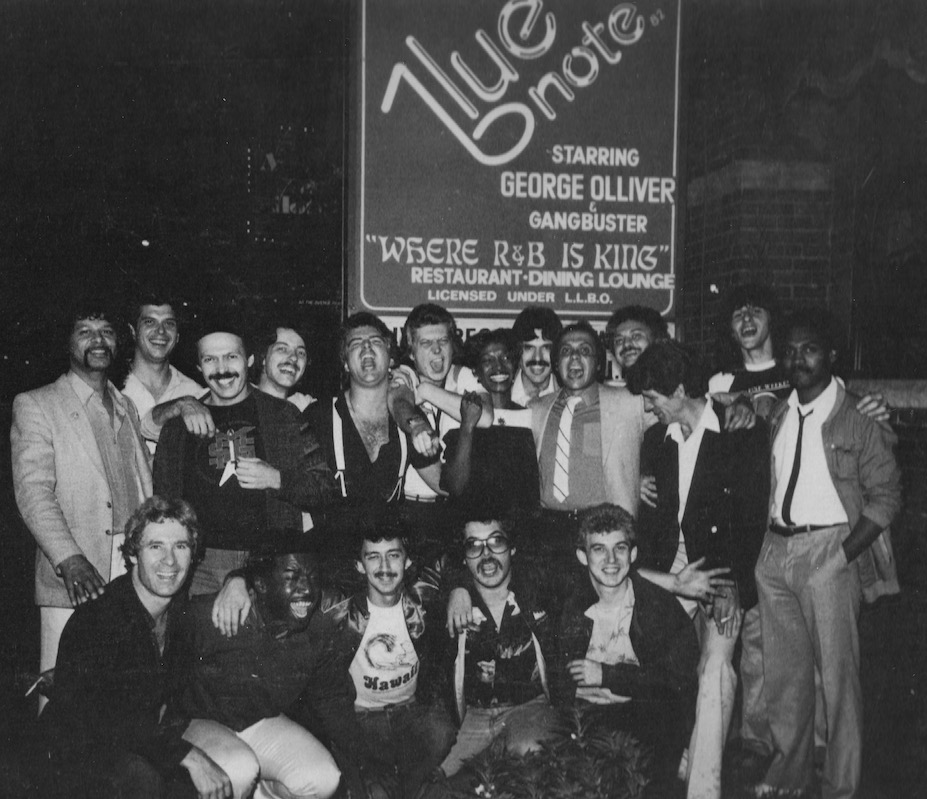

As Whitey & the Roulettes, Glan and Olliver became the house band at an after-hours venue on Yonge Street called Club Bluenote, which billed itself as the place “where R&B is king.” Olliver fell under the spell of James Brown after seeing the Please Please Please singer at a concert in Newark, N.J. Soon, he was channelling Brown’s dynamic performance style as his own.

Recalls singer Shawne Jackson, who briefly dated Olliver: “I met George at the Bluenote in 1965 and thought he had a marvellous voice and sang just like a black guy. And his stage show was amazing too. He thought he was James Brown – he really did. He was a whirling dervish. I’d never seen anyone like him.”

With the addition of future Hall of Fame guitarist Domenic Troiano, the Bluenote’s house band evolved into the Five Rogues, adopted a strict rehearsal regimen and soon became a tight, polished R&B outfit and one of Toronto’s most successful bands, opening for the Rolling Stones and Wilson Pickett. The arrival of manager Randy Martin, a showbiz genius born Rafael Markowitz and a former children’s clown on TV’s The Randy Dandy Show, transformed the Rogues into the Mandala. With a well-orchestrated stage show and an equally well-hyped promotional package, the band became a phenomenon – complete with screaming, fainting girls.

With the addition of future Hall of Fame guitarist Domenic Troiano, the Bluenote’s house band evolved into the Five Rogues, adopted a strict rehearsal regimen and soon became a tight, polished R&B outfit and one of Toronto’s most successful bands, opening for the Rolling Stones and Wilson Pickett. The arrival of manager Randy Martin, a showbiz genius born Rafael Markowitz and a former children’s clown on TV’s The Randy Dandy Show, transformed the Rogues into the Mandala. With a well-orchestrated stage show and an equally well-hyped promotional package, the band became a phenomenon – complete with screaming, fainting girls.

Watch Mandala's Five Steps to Soul

Olliver once described to this writer the Mandala’s “soul crusade,” which began in darkness with just the sound of Glan’s drumbeat: “We’d always start with our backs to the audience. Randy would be backstage with a microphone, introducing us one by one. As each of us was introduced, we’d turn around and start playing. And then the strobe lights kicked in. It was all quite a buildup.”

A discovery at Toronto’s Hawk’s Nest by Bo Diddley led to a recording deal with Chess Records and the Troiano-penned hit single “Opportunity,” which featured Olliver’s “Lost Love” on the flip side. With Martin’s acumen, the Mandala was soon taking L.A.’s Sunset Strip by storm, playing to packed houses at the Hullabaloo and the Whiskey a Go Go, with celebrities like Herb Alpert, Nancy Sinatra and Steve McQueen in attendance. Olliver’s splits and knee drops proved so punishing to his striped pants that Marilyn Brooks, the band’s Toronto designer, had to apply knee patches and a stretchy fabric to the crotch.

As the Mandala’s popularity grew, tensions within the group did as well. A rift arose over musical direction, with Troiano wanting to move toward rock and Olliver wanting to lean more heavily into soul. In the end, Olliver quit just before a coveted deal with Atlantic Records, home of Aretha Franklin and many R&B greats, led to the Mandala’s Soul Crusade album, featuring the hit single “Love-It is” and new singer Roy Kenner on vocals.

Rather than rue his missed opportunity, the tireless Olliver threw himself into numerous projects. He formed a 10-piece soul band the Children, followed by his group Natural Gas, whose self-titled album included the popular track “All Powerful Man.” Under his own name during the 1970s, he released the singles “I May Never See You Again” and “Don’t Let the Green Grass Fool You.” He also performed with singer Bobby Dupont in an R&B duo called the Royals.

In 1982, Olliver opened a new edition of Club Bluenote in Toronto, at 128 Pears Ave., and led its house band, Gangbuster. Like its predecessor, which had played such a formative role for him, the new Bluenote was a bastion of soul music and quickly became the hottest club in town, with lineups out to Avenue Road six nights a week. Troiano, who died in 2005, was so taken with the venue that in 1983 he produced the Live at the Bluenote album, featuring Olliver, Jackson, Kenner and Jayson King.

In 1982, Olliver opened a new edition of Club Bluenote in Toronto, at 128 Pears Ave., and led its house band, Gangbuster. Like its predecessor, which had played such a formative role for him, the new Bluenote was a bastion of soul music and quickly became the hottest club in town, with lineups out to Avenue Road six nights a week. Troiano, who died in 2005, was so taken with the venue that in 1983 he produced the Live at the Bluenote album, featuring Olliver, Jackson, Kenner and Jayson King.

Recalls keyboardist Lou Pomanti, whom Olliver recruited for the band: “The Bluenote gave George a great second act, but he was also selfless and generously featured guest stars every night, either local artists or international acts like Etta James. He really made the Bluenote the classiest of nightclubs and the place to be in Toronto.”

After a life-changing event in the late 1970s, Olliver turned increasingly toward Christianity and started his Joy ministry and the Caught Away gospel group. Singer Cathy Young, who sang for 20 years with the group, observed a different performer in Olliver than the one she knew from his Mandala days. “It was a softer George, a more vulnerable and open George,” Young said. “He was still a demanding leader, totally professional and dedicated, but he’d loosened up a little.”

Following a Juno Award nomination for his 1987 album Dream Girl, Olliver and his wife, Pat Olliver (née Hunter), travelled to Shuya, Russia, northeast of Moscow, and adopted a son and daughter (Olliver already had one son, Javen, the result of an earlier relationship). In 2008, he released the album George Olliver’s Gospel Soul – Look Up. Around 2015, during a Caught Away performance in downtown Toronto, Olliver was stricken with Bell’s palsy, which left one side of his face paralyzed and caused it to droop. But he got through the show and continued doing live performances until late last year.

With more than 60 years in the entertainment field, Olliver could have rightfully accepted the title of “hardest working man in show business” that many, including legend Ronnie Hawkins, tried to bestow on him. But out of deference to soul king James Brown, who was also known for his indomitable work ethic, Olliver was happy just to be called the “Blue-Eyed Prince of Soul.”

George Olliver was predeceased by his brother, Brent Olliver, and leaves his sister, Diane Lindsay; wife, Pat; sons, Javen and Shane; daughter, Seraphina; and several grandchildren.