Gordon Lightfoot Book, Music and More!

Ronnie ‘Bop’ Williams - Unheralded reggae pioneer helped define the genre

He was one of the early architects of Jamaican music – a guitarist, bass player, songwriter, arranger and producer whose contributions to hundreds of recordings helped to shape reggae and popularize it around the world. He played with Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, Johnny Nash and Toots and the Maytals, and worked for such famous studio owners as Duke Reid, Bunny Lee and Lee (Scratch) Perry, and the Trojan, Treasure Isle and Upsetter record labels. Yet the name Ronnie (Bop) Williams is barely known outside of reggae circles.

Part of the reason for the near anonymity was Mr. Williams’s own modesty. A soft-spoken man, he came from extremely humble roots in rural Jamaica, teaching himself to play on a guitar fashioned from a large sardine can. Although he later added unique parts to some of reggae’s best-known songs, including Mr. Marley’s “Small Axe,” “Kaya,” “Trenchtown Rock,” “Sun is Shining” and “Don’t Rock My Boat,” Mr. Williams, who lived and worked in England before settling in Canada, was never inclined to promote himself. It didn’t help that he wasn’t always credited for his contributions – or that, when he was, variations and misspellings of his name often appeared.

Mr. Williams, 78, died in Toronto on April 18, of complications from diabetes. His death prompted musicians and historians to pay tribute to a prolific, nearly forgotten artist whose legacy remains largely overlooked.

Mr. Williams, 78, died in Toronto on April 18, of complications from diabetes. His death prompted musicians and historians to pay tribute to a prolific, nearly forgotten artist whose legacy remains largely overlooked.

“Ronnie Williams is the most wildly unheralded figure in Jamaican music,” claims Canadian keyboardist Jason Wilson, author of King Alpha’s Song in a Strange Land: The Roots and Routes of Canadian Reggae. “His rhythm-guitar sound really helped to define reggae.”

Sly Dunbar, the legendary Jamaican drummer who has played on albums by Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones and others, agrees. “Ronnie Bop was a great guitarist with his own style,” Mr. Dunbar said via text. “You could really tell that it’s him playing on those Treasure Isle records.”

London-based writer David Katz encountered many examples of Mr. Williams’s legacy while researching his book Solid Foundation: An Oral History of Reggae. In particular, he cites the guitarist’s role in evolving reggae from rocksteady and helping celebrated bassists Robbie Shakespeare and Aston (Family Man) Barrett get their start in music. He contributed phased guitar to the Heptones’ Party Time album and played the atmospheric wah-wah guitar opening to Junior Murvin’s “Police and Thieves,” later covered by the Clash.

“Ronnie Williams’s distinctive guitar playing graced many important records, not just early work by Bob Marley and the Wailers,” says Mr. Katz, who is also Lee (Scratch) Perry’s biographer. “And Ronnie really helped reggae become established in the U.K. and Canada and should be remembered as a true pioneer.”

Mr. Williams was born Lorraine Ranford Williams on Nov. 8, 1942, in Spanish Town, Jamaica, outside of Kingston, the middle of five children born to Bazil Williams and his wife, Elijah (née Miller). His father died when he was a small boy and he was raised by his mother, a secretary for a local Seventh Day Adventist church, and his grandmother, Margaret Miller.

Young Rannie busked on the streets, dancing and “brushing” his handmade guitars for loose change. “When I say ‘brush,’” he told writer Rich Lowe, “that means strumming. It jus’ like a down-and-up stroke while I move my body – we used to call ‘fling it back’ those days.”

That down-and-up stroke and its “chicka-chicka” sound became a defining part of the music. And the sight of a dancing, guitar-playing kid earned him the nickname Ronnie Bop (although he was still sometimes known as Rannie, or Ranny, and even Rannie Bop). Mr. Williams was then discovered by saxophonist Tommy McCook, who promptly recruited him to join his popular Supersonics band. Shortly after, the talented guitarist also began working for Mr. Reid, playing on a steady string Treasure Isle productions such as “Ba Ba Boom” by the Jamaicans, which won the island’s 1967 Independence Festival Song Competition. Mr. Williams was on his way.

“Ronnie became the big session man,” recalls Tony King, then a 17-year-old Kingston musician, “and he told me he was going to become a producer and make his own records. When he did, I started taking his discs around to jukeboxes and shops and became the walking record distributor for Ronnie Bop.”

While still playing with Mr. McCook’s Supersonics, with whom he toured Canada in 1969, performing at Toronto’s Queen Elizabeth Ballroom on the CNE grounds for a Thanksgiving concert, Mr. Williams joined a Jamaican studio backing band called the Hippy Boys, which included bassist Mr. Barrett. One of their instrumentals served as the basis for the Harry J Allstars’ hit “The Liquidator,” which became a popular English soccer anthem. Soon, the group was recording its own singles, many of them produced and written by Mr. Williams.

While still playing with Mr. McCook’s Supersonics, with whom he toured Canada in 1969, performing at Toronto’s Queen Elizabeth Ballroom on the CNE grounds for a Thanksgiving concert, Mr. Williams joined a Jamaican studio backing band called the Hippy Boys, which included bassist Mr. Barrett. One of their instrumentals served as the basis for the Harry J Allstars’ hit “The Liquidator,” which became a popular English soccer anthem. Soon, the group was recording its own singles, many of them produced and written by Mr. Williams.

Members of the Hippy Boys formed the core of two subsequent backing groups assembled by Mr. Perry: the Upsetters and the Wailers. Mr. Williams helped to make the Upsetters’ song “Return of Django,” a Top 10 U.K. hit in 1969. And his guitar playing is all over the Wailers’ backing of Mr. Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingstone on the songs that formed the groundbreaking Soul Rebels and Soul Revolution albums released over the next two years.

In 1971, after playing with Mr. Nash and Mr. Marley, Mr. Williams settled in England and worked extensively for Pama Records, producing many sessions and playing guitar and bass. One of his biggest successes was “I Can’t Resist Your Tenderness,” a 1974 song he wrote and produced for the singer Ginger Williams that kick-started the lovers rock subgenre in the U.K. He also formed the band X-Press and scored another hit backing singer Winston Reedy on “Breakfast in Bed.”

By the end of the seventies, Mr. Williams had moved to Toronto, already a popular home for Jamaican immigrants and reggae stars such as Jackie Mittoo, Leroy Sibbles and Lord Tanamo. In 1982, Mr. Williams opened Record Corner in Kensington Market, directly opposite a record store owned by another Jamaican expat musician, Stranger Cole. With bass-driven reggae tracks from their respective sound systems shaking the ground around them, Mr. Williams and Mr. Cole created what came to known by locals as the Market’s “wobble zone.”

By the end of the seventies, Mr. Williams had moved to Toronto, already a popular home for Jamaican immigrants and reggae stars such as Jackie Mittoo, Leroy Sibbles and Lord Tanamo. In 1982, Mr. Williams opened Record Corner in Kensington Market, directly opposite a record store owned by another Jamaican expat musician, Stranger Cole. With bass-driven reggae tracks from their respective sound systems shaking the ground around them, Mr. Williams and Mr. Cole created what came to known by locals as the Market’s “wobble zone.”

Lloyd Delpratt, a Jamaican keyboardist who had emigrated during Canada’s centennial year, remembers meeting Mr. Williams shortly after he arrived. “He was a tall, good-looking man with a big, smiling face – very gentle and easy to talk to,” Mr. Delpratt says. “I liked him right away.”

The two knew of each other by reputation – Mr. Delpratt had preceded Mr. Williams in Mr. McCook’s Supersonics – and soon they were working together in Toronto. In 1985, their contributions on bass and keyboards helped win singers Liberty Silver and Otis Gayle the first Juno Award for a reggae recording, for the song “Heaven Must Have Sent You.”

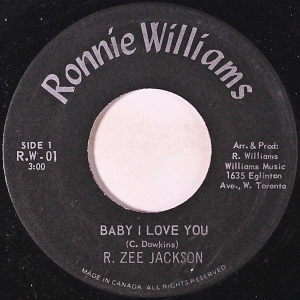

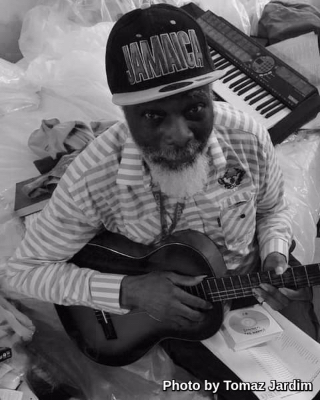

That same year, Mr. Williams won two Canadian Reggae Music Awards for best bassist and producer for his work on singer Lincoln Carroll’s For the Rest of Our Lives album, released on his own Ronnie Bop label. He produced many others in the local reggae community, including Carol Brown, the Webber Sisters and R. Zee Jackson, who remembers Mr. Williams’s strong musicality. “Ronnie had an amazing ear and never played the same old thing as everyone else,” Mr. Jackson recalls. “His melodies and tones on guitar and bass were always fresh and a little different.”

That same year, Mr. Williams won two Canadian Reggae Music Awards for best bassist and producer for his work on singer Lincoln Carroll’s For the Rest of Our Lives album, released on his own Ronnie Bop label. He produced many others in the local reggae community, including Carol Brown, the Webber Sisters and R. Zee Jackson, who remembers Mr. Williams’s strong musicality. “Ronnie had an amazing ear and never played the same old thing as everyone else,” Mr. Jackson recalls. “His melodies and tones on guitar and bass were always fresh and a little different.”

Others remember the generous Ronnie Bop spirit.

Jason Wilson was a 15-year-old aspiring keyboardist from Toronto’s Downsview area when Mr. Williams asked him and another teenager, Andru Branch, to join his Yah Wah Deh (Here We Are) band in 1986.

“Here was this Jamaican legend in his 40s taking me, this Scottish kid, under his wing,” Mr. Wilson recalls. “I learned so much about reggae from the man and will always remember his patience and generosity.”

Mr. Williams was also an imposing, central figure in Awanjah (One God), a roots-rock-reggae band with singer Alan Besley and bassist Carlton Dinnall. In 1988, the group released one album, Visionary Revolutionist, recorded in Jamaica’s Mixing Lab studio.

In his later years, Mr. Williams fell on hard financial times due to his failing health and was living in a single room in subsidized housing. After his death, a GoFundMe campaign was launched by a friend’s daughter to cover his funeral expenses and debts from medical bills.

In his later years, Mr. Williams fell on hard financial times due to his failing health and was living in a single room in subsidized housing. After his death, a GoFundMe campaign was launched by a friend’s daughter to cover his funeral expenses and debts from medical bills.

According to his musical colleagues, Mr. Williams never received all the royalties he was due from his compositions or recordings. Others say that aside from recording-industry injustices, it was Mr. Williams’s own humility and reserve that held him back.

“It was only after we’d been with him a few weeks in Yah Wah Deh that we learned Ronnie had played with Bob Marley,” Mr. Wilson recalls. “I wish he’d been more vocal about his accomplishments, because he’d be more celebrated today.”

Mr. Williams was predeceased by one daughter, Petrona, and leaves three brothers, Lewin, Percy and Kay; five children, Sophia, Tracey, Duane, Junior and Telicia; his former common-law wife, Monica Tomlinson; and ex-wife, Annette Williams.

Originally published in The Globe and Mail 10 May 2021