Music journalism, books and more

Liner Notes: Whiskey Howl - Whiskey Howl

Canadians have long had a love affair for the blues. In the 1970s, artists from Vancouver’s Powder Blues and Halifax’s Dutch Mason to Montreal’s Offenbach and Winnipeg’s Big Dave McLean thrilled audiences with their interpretations of the 12-bar form. The blues feeling has always been especially strong in Toronto, where a close proximity to Chicago and Detroit and regular appearances by major U.S. blues artists fostered a deep connection with the music. Three of Canada’s earliest and most successful blues groups hailed from Toronto and nearby Hamilton, including Downchild Blues Band, McKenna Mendelson Mainline and Crowbar with King Biscuit Boy. Into this blues-loving milieu came Whiskey Howl.

Canadians have long had a love affair for the blues. In the 1970s, artists from Vancouver’s Powder Blues and Halifax’s Dutch Mason to Montreal’s Offenbach and Winnipeg’s Big Dave McLean thrilled audiences with their interpretations of the 12-bar form. The blues feeling has always been especially strong in Toronto, where a close proximity to Chicago and Detroit and regular appearances by major U.S. blues artists fostered a deep connection with the music. Three of Canada’s earliest and most successful blues groups hailed from Toronto and nearby Hamilton, including Downchild Blues Band, McKenna Mendelson Mainline and Crowbar with King Biscuit Boy. Into this blues-loving milieu came Whiskey Howl.

Formed in 1969, Whiskey Howl emerged from Toronto’s suburbs to become one of the premier acts of the CanCon era of the early ’70s. Led initially by harmonica player John Bjarnason, the group landed some highly prestigious gigs, opening for Led Zeppelin, performing with American blues legends and appearing with John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band and many others at the historic Toronto Rock & Roll Revival show. During its incarnation fronted by Bjarnason’s replacement, Michael Pickett, Whiskey Howl scored an enviable major-label deal with Warner Bros. and recorded an acclaimed self-titled album in 1972, issued here for the first time on CD. A quarter of a century after its release, the recording still packs a formidable punch.

Bjarnason was one of Toronto’s earliest blues aficionados, studying the styles of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf whenever they performed at the Colonial Tavern on Yonge Street. Two local musicians provided him with further education. “I got my background in the blues from Chris Whiteley, who I went to school with at Don Mills Collegiate,” Bjarnason recalls. “The first band I play in was actually called the Don Mils Blues Band, which was just a neighborhood group.” Before long, the aspiring musician was down in Yorkville’s hippie haven, taking guitar lessons from Joe Mendelson. Bjarnason’s next band, The Back Door, went further afield, playing larger venues like the Broom & Stone with the likes of Shawne and Jay Jackson & the Majestics.

Whiskey Howl grew out of the ashes of yet another Bjarnason outfit, the popular Yorkville band Sherman & Peabody. Joining Bjarnason and guitarist Peter Boyko was a robust singer named John Witmer, who brought along bassist Gary Penner and drummer Ron Sullivan, with whom he played in a Downsview group called Harry’s Blues Band. With the initial lineup intact, Whiskey Howl debuted at Yorkville’s Night Owl coffeehouse on July 28, 1969. Before the band was even a month old, it was opening for Led Zeppelin when the British band appeared at Toronto’s Rock Pile, before a sold-out audience of 1,200 frenzied fans. One month after that, Whiskey Howl joined Lennon’s Revival show at Varsity Stadium, which infamously featured Alice Cooper, who allegedly bit the head off a chicken. The Toronto band, with new drummer Wayne Wilson replacing Sullivan, appeared twice on the bill, playing its own set and backing the eccentric British singer Screaming Lord Sutch.

“During the show, we were rehearsing with Lord Sutch in a room under the bleachers, running through ‘Good Golly, Miss Molly,’” recalls Bjarnason. “All of a sudden, the double doors to the room burst open and a tall black man with a pompadour hairdo storms in, wearing a flowing cape, and yells ‘You’re playin’ my song! You’re playin’ my song!’ It turned out this was Little Richard, who was also on the bill, along with Bo Diddley, Jerry Lee Lewis and many others. We couldn’t believe our eyes.” Witmer remembered getting drunk backstage with a guy who turned out to be James Pankow, trombonist-arranger for Chicago, and sobering up to the sound of 100 rumbling Vagabond Harleys that were escorting The Doors’ limousine to the dressing rooms.

“During the show, we were rehearsing with Lord Sutch in a room under the bleachers, running through ‘Good Golly, Miss Molly,’” recalls Bjarnason. “All of a sudden, the double doors to the room burst open and a tall black man with a pompadour hairdo storms in, wearing a flowing cape, and yells ‘You’re playin’ my song! You’re playin’ my song!’ It turned out this was Little Richard, who was also on the bill, along with Bo Diddley, Jerry Lee Lewis and many others. We couldn’t believe our eyes.” Witmer remembered getting drunk backstage with a guy who turned out to be James Pankow, trombonist-arranger for Chicago, and sobering up to the sound of 100 rumbling Vagabond Harleys that were escorting The Doors’ limousine to the dressing rooms.

Over the next six months, Whiskey Howl continued to land illustrious gigs, sharing the stage with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band at York University and Johnny Winter at Massey Hall, backing Big Mama Thornton on CBC’s Rock 1 TV special, appearing with jazz drummer Elvin Jones and opening for Chuck Berry at Convocation Hall. But the Toronto group’s dream concert was Blue Monday, a blues concert at Massey Hall featuring the legendary Lonnie Johnson, Buddy Guy and Bobby Blue Bland. “We were completely in awe of these guys,” admits Bjarnason. “The show turned out to be the last public appearance for Lonnie Johnson, who had moved to Toronto and opened his own club in Yorkville called Home of the Blues. So we felt privileged to be a part of it.”

In the spring of 1970, Whiskey Howl entered the Toronto Sound recording studio to lay down four songs, including two blues standards and a pair of original songs by Witmer. Financed by the band itself, these recordings were strictly demos and never released. However, the group, a big favorite of Globe and Mail rock critic Ritchie Yorke, came close that summer to landing a record deal. “Ritchie was determined that we were going to make an album,” recalls Bjarnason. “He introduced us to Frank Davies, who owned Daffodil Records (home of Crowbar and King Biscuit Boy). But all Frank offered us was the chance to record a single. Being young and naïve, I turned it down and walked out. In retrospect, I should’ve done it to get our foot in the door.”

Whiskey Howl’s record deal didn’t come for another year. In the meantime, Bjarnason left the group, opting to pursue a career as a chiropractor. Michael Pickett, a talented blues harmonica player who’d played with Witmer in Harry’s Blues Band, stepped in to fill the void. More lineup changes were to follow. A new chapter in the group’s blues odyssey was about to begin.

* * * * *

One of Whiskey Howl’s first significant gigs after Bjarnason’s departure was at New York’s Village Gate. The Greenwich Village club, made famous through appearances and recordings by John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Nina Simone and Aretha Franklin, hosted the young Toronto band for a week-long stint in January, 1971. “We were totally jazzed about being in New York and playing at such a prestigious venue,” recalls Pickett. “It really felt like we’d made it.”

Back home, the buzz about the band was growing. Whiskey Howl began alternating weeks at Grossman’s Tavern on Spadina Avenue with the already established Downchild Blues Band. Fronted by guitarist and harmonica player Donnie Walsh and his brother, singer Rick “Hock” Walsh, Downchild was drawing crowds to Grossman’s to hear the band’s brand of jump- and Chicago-style blues. “We looked up to them,” admits Pickett. “Their presence on the scene set the bar high for blues in Toronto and really affected Witmer, myself and others in our group.” As a bastion for blues, Grossman’s served as a hothouse for Whiskey Howl’s flowering talents. Members of Muddy Waters’ and Howlin’ Wolf’s bands would drop over, whenever they were in town performing at the Colonial, and sit in with the group.

One particular visit by a U.S. bluesman proved to be a turning point for Pickett. “I was struggling to get the best sound out of my amp,” Pickett recalled. “I didn’t have the tone or attack that I wanted.” That all changed after legendary harmonica player James Cotton showed up. “I invited Cotton to play and he was in his prime at the time, just a monster,” says Pickett. “He walks over, takes the microphone, doesn’t change the settings on the amp or anything, and starts playing. It felt like the walls were going to come tumbling down. It was unbelievable. It sounded like a freight train running through Grossman’s. I realized then that it’s not the mike or the amp that counts, it’s what you do with it. That was a major lesson for me.”

Whiskey Howl was soon landing opening slots on shows with Cotton and Waters, and played a week-long engagement at the Colonial with the “Queen of the Blues,” singer Koko Taylor. But the band’s biggest break came when Howl manager Ed Glinert scored the group a record deal with Warner Bros. Signed by Warner A&R man John Pozer, a former DJ who had run Ottawa’s Sir John A record label, the band was hooked up with U.S. producer Johnny Sandlin, best known for his work with The Allman Brothers, for sessions in Toronto.

By now, the group had undergone more personnel changes. Boyko and Penner departed, with guitarist Dave Morrison and bassist Rick Fruchtman coming in as their replacements. The new quintet entered Eastern Sound studios with Sandlin and a collection of blues covers and original tunes. Warner gave the band plenty of artistic freedom. “Pozer told us, ‘We don’t want to get in your way and stifle your creativity,’” recalled Morrison. “He basically said to us, ‘As long as you’re not stark raving maniacs in the studio, we’re happy to let you do your thing.’” Sandlin, meanwhile, was the epitome of a laid-back southern gentleman. “Johnny had worked in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where they make real records,” says Pickett. “The main thing that he did with us was he kept telling us to lay back. He’d say, ‘Don’t push it, don’t rush the groove.’ That helped to define our sound on the album.”

By now, the group had undergone more personnel changes. Boyko and Penner departed, with guitarist Dave Morrison and bassist Rick Fruchtman coming in as their replacements. The new quintet entered Eastern Sound studios with Sandlin and a collection of blues covers and original tunes. Warner gave the band plenty of artistic freedom. “Pozer told us, ‘We don’t want to get in your way and stifle your creativity,’” recalled Morrison. “He basically said to us, ‘As long as you’re not stark raving maniacs in the studio, we’re happy to let you do your thing.’” Sandlin, meanwhile, was the epitome of a laid-back southern gentleman. “Johnny had worked in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where they make real records,” says Pickett. “The main thing that he did with us was he kept telling us to lay back. He’d say, ‘Don’t push it, don’t rush the groove.’ That helped to define our sound on the album.”

Sandlin brought in a young hotshot pianist named Chuck Leavell, who later became a keyboard session player for Eric Clapton and The Rolling Stones. The producer also added a horn section, made up of local players Keith Jollymore, Dave Woodward and Phil Alperson, to help round out the Howl sound on Louis Jordan jump-blues standards like “Caldonia,” “Early in the Morning” and “Let the Good Times Roll” and a down-tempo blues number by Memphis Slim called “Mother Earth.” Witmer-penned originals like “Down the Line” and “Jessie’s Song,” about his first-born son, feature Witmer’s bluesy howl and Morrison’s rootsy guitar picking respectively, while Pickett shines on harmonica and vocals on his own “One Hot Lady.”

Two of the album’s highlights are the band’s composition “Pullin’ the Midnight,” featuring dazzling solos from Pickett and Leavell, and the group’s rendition of “Rock Island Line.” It was a brave move for an electric blues band to sing the Leadbelly standard in acapella four-part harmony. “We didn’t think of ourselves strictly as a blues band,” insists Pickett. “None of us were purists. We loved all kinds of music, from folk and blues to jazz and r&b. We were very roots-oriented and that always showed in our sound.”

* * * * *

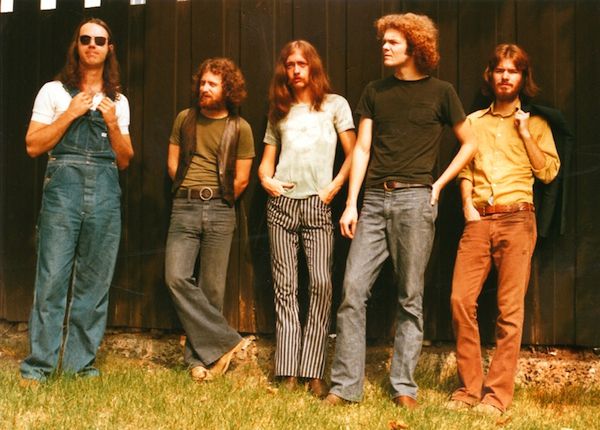

When Whiskey Howl’s self-titled album came out in the summer of ’72, with a cover shot of the group standing on Spadina Avenue outside of Grossman’s, it quickly garnered rave reviews and airplay on FM stations across the country. The band gigged extensively following its release, with many trips to Sudbury and other parts of northern Ontario and a national tour with Dr. Music, performing at autumn fairs like Toronto’s CNE, Vancouver’s PNE and Edmonton’s Pioneer Days. In particular, Morrison fondly recalls shows in Banff and a week-long gig in Vancouver that turned into a month-long residency at the Pharaoh’s Retreat club in Gastown. “The thing about our band was that we dug each other and loved working together,” says Morrison. “It was real ensemble playing.”

Sadly, the band had a short life, breaking up in 1974 and reforming briefly in ’76 and again in ’81 before finally calling it quits. Glinert had parted ways with the group before the album release, leaving Whiskey Howl without experienced management to take it to the next level. Momentum was lost and another promising Canadian band group with potential to become major stars on the U.S. circuit fell by the wayside. “We were young and stupid,” admits Morrison, “and had no idea of the business. But we had a good time while it lasted.”

Whiskey Howl remains one of the great success stories of the early CanCon era, a blues band that enjoyed a large, loyal following, appeared on legendary concert bills and left one memorable studio album. So sit back and relax, ’cause Whiskey Howl is back in town. Let the good times roll.